the suburb and the sky

industrial colours

black and white

scenes from the street

Leaving the State Library behind, our wonderful guide, Bronwen, led us down Murray Street past “Murray House”, to the corner of Liverpool Street, where we found the former MLC Building.

It was designed by Philp Lighton Floyd and Beattie for MLC. I had to google ‘MLC’ as I’m not sure what it stands for (other than knowing it’s easily confused with CLM, whose building on the corner of Macquarie and Elizabeth Street was where we saw a ghost sign on Saturday). I suspected the words “mutual” and “life” might make an appearance and, indeed, MLC was once known as Mutual Life & Citizens Assurance Company Limited.

The building was constructed in two stages, with the first five storeys built (according to my records) in 1958, which means it pre-dates the library. The remaining floors were added in about 1977.

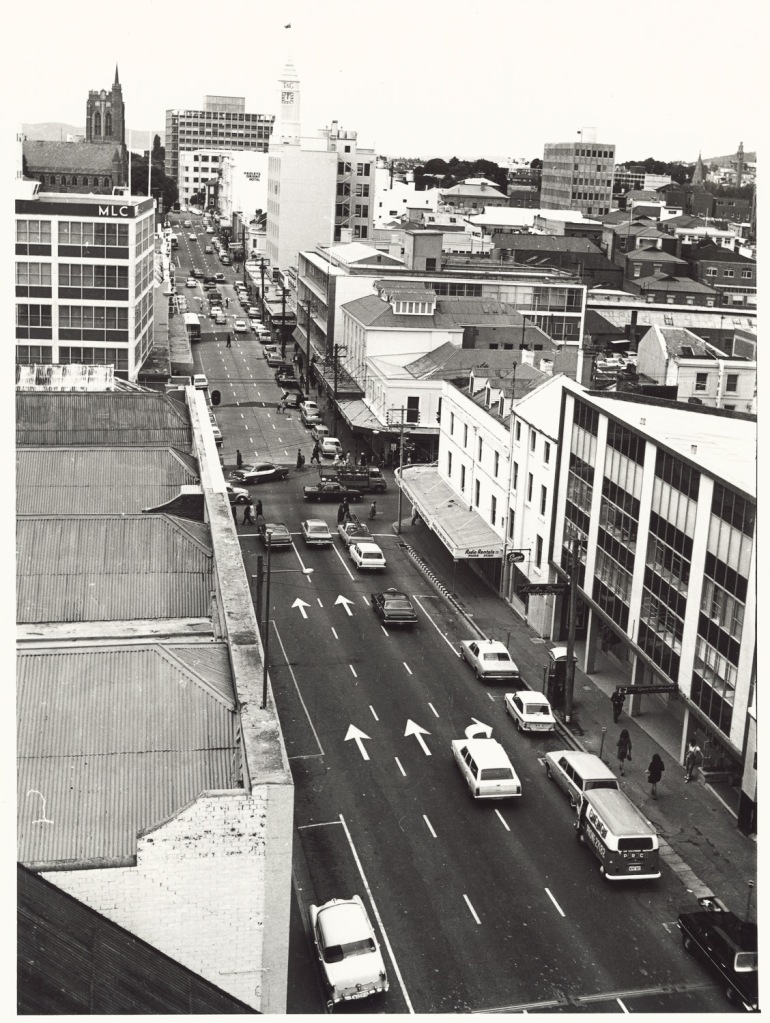

I found the above photo in the library, which shows what the MLC building looked like before the top floors were added. (It looks like it might have been taken from the library.) There are a few other buildings in Hobart where this approach was taken. What is now Construction House in Bathurst Street and former 34 Davey Street are two that come to mind.

I was lucky to have had a tour of this building through Open House in 2018, which took in the view of the city from the roof.

The building also has this interesting extension on the first floor, which I think Bronwen said was part of the original design. And of course, the obligatory relief sculpture to show MLC’s care for their customers.

Further along Murray Street is Jaffa House, which wasn’t on our official list of stops but we stopped there anyway.

It was designed by Jim Moon of Bush Parkes Shugg and Moon, and built in 1971-72. It was originally the Savings Bank of Tasmania headquarters, and is known as Jaffa because of its colour.

Our next stop was AMP House on the corner of Collins and Elizabeth Street. It will always be AMP to me, never NAB, despite what the sign on the side says.

It was designed by Richard Crawford of Crawford Shurman Wegman Architects and competed in 1968.

This is a delightful building that can almost be seen in two parts: the tower and the podium on which it sits. I’ve often thought that the podium by itself would make a lovely small brutalist building.

You can see the relationships between the tower and the podium more clearly from higher up, like in this photo I made from the roof on the neighbouring CML Building during Open House 2018. (I did a lot of rooftops that year!)

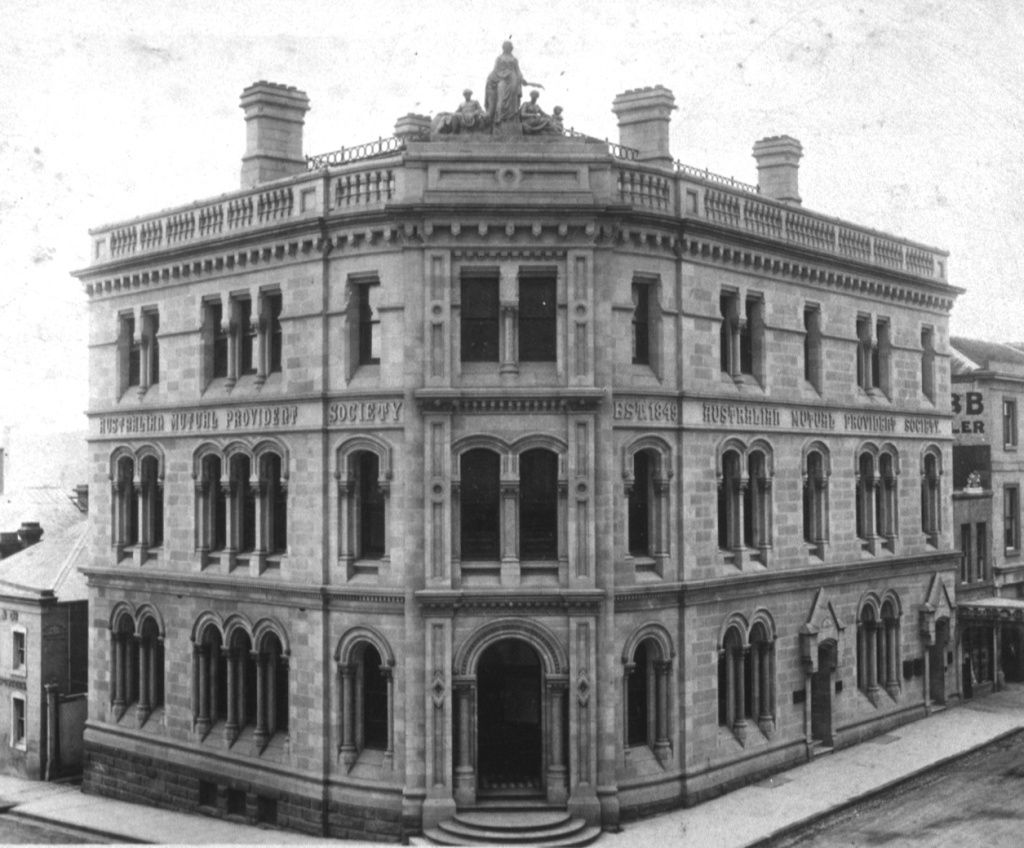

AMP is the Australian Mutual Provident Society, and it had a small office building on this site prior to 1881, when its new building was constructed.

This building was extended and had another floor added in 1913. Bronwen said that in the 1960s, AMP decided it wanted to own the tallest building in Hobart, so it had the 1881 building demolished and replaced with the current one. One of the archways from the old building is now located in the Botanical Gardens.

The facade features the Tom Bass relief sculpture “Amicus certus in re incerta – A sure friend in an uncertain event”, which is similar to the one on the side of Sydney’s AMP building. This one has a stylised map of Tasmania in the centre of arms encircling the Goddess of Plenty watching over the father, mother and child.

Just around the corner on Macquarie Street, is the Reserve Bank Building, which we learned about on a 2020 Open House walking tour.

This building was completed in 1978, and Bronwen noted its recessed corners. (She loves recessed corners and pointed them out everywhere we went). What I remember about this building is that they wanted to keep it simple and inexpensive because money was tight at the time, and it wouldn’t have been a good look for the government to go splashing cash around for a fancy new bank building.

It was awarded the ‘Enduring Architecture Award’ at the 2012 Tasmanian Architecture Awards.

Bronwen pointed out the recessed area to the left of the building that was kept aside for the public artwork, which in this case is Stephen Walker’s wonderful Antarctic Tableau.

Our final stop was the fabulous Lands Building in the next block.

It’s a very neat symmetrical design with some kind of escape hatch on the second to top floor that no one has ever been able to explain. (Look closely!)

Another example from the 1970s (1976, I believe), it is, like other brutalist structures, grounded and earthy, which, Bronwen observed, seems appropriate for something called the Lands Building.

I think it could be taller.

And that was the end of the tour.

It was great to meet someone who loves these buildings so much, and I agree with Bronwen that we need to find out more about them. I’m certainly enjoying uncovering their history from random places, but often all I can find is little snippets, as there isn’t a lot of readily available information about many of these buildings. It’s fun to search though! There are many rabbit holes . . .

Before we left, Bronwen asked if there was any interest in more tours of other modernist buildings and the answer was a very enthusiastic ‘yes’, so hopefully next year we’ll see her again.

If you can’t already tell from the majority of my photos, I’m rather fond of modernist buildings. So I was very excited when I saw there was a modernism walking tour on Open House weekend.

I’d told Lil Sis when we were negotiating the booking system that I didn’t care about anything else as long as I got onto this tour. We had booked onto a modernism tour a couple of years ago and it had been cancelled at the last minute because the architect had broken their toe and couldn’t manage the walk.

But no such disaster this time, and we met architect Bronwen Jones outside the State Library on Sunday afternoon.

Bronwen describes herself as a flâneuse, a female flâneur, the person who walks around the streets, observing urban life. I’ve often felt connected to this term but the one I use more often to describe myself is ‘urban bushwalker’. To my mind, it’s the same thing. Though maybe the original flâneurs walked with a sketchbook and I walk with my camera.

Bronwen is passionate about modernism and observed that, unlike the old sandstone buildings that dominate Tasmania’s landscape, there has been very little research done into these mid-20th century structures. As a result we don’t know a lot about them and there’s a real risk of them being demolished with their stories untold. It’s happened to far too many of these buildings already.

We began our tour at the Stack, the wonderful 1970s brutalist addition to the State Library (which you might recall was originally housed in the Carnegie Building we saw on the Signs of Hobart tour). It’s a most distinctive building, and there’s a video floating round in the archives that shows it being built.

It took me many years to work out that when an item’s location in the library catalogue said “Stack” it actually meant the item was in this building not, as I’d imagined, that it was sitting in a stack of other books on the floor . . . That only happens in my house. The library would not do this.

Now that we have that cleared up, we were accompanied on the first part of the tour by Nina, one of Open House’s official photographers, who I’d met at the drawing workshop on Friday.

And at last, finally, several years after she had photographed me photographing a building completely unaware, I got my chance to return the favour. You have to be quick to do this though. She knows exactly what you’re doing most of the time!

So, back to the Stack.

This building is raw, honest and, as Bronwen pointed out, designed with minimal windows to keep all the precious archival records away from the sunlight. She said it was always the intention for this section to be added when the library building was designed in the late 1950s, but it wasn’t completed until around 1971.

The State Library building itself was designed by the Melbourne architect John Scarborough, who also designed the Morris Miller Library at the University. It was opened in 1962.

As we admired this fabulous building, Bronwen spoke about the context within which the modernist buildings came to be. There is much written on this. It was a time following post-war austerity, when architects (and everyone else) were able to travel internationally and bring back new ideas, and new immigration waves of people bringing ideas from their homelands with them. This included new design concepts, new materials like glass, steel and concrete, and new technology, including pre-fabrication.

And standardisation. There’s a lot of that. Fin. Glaze. Panel Repeat.

Bronwen said there is a lot of horizontal lines and regularity in these designs, but not necessarily with the axial symmetry you’d see in a Georgian design. The idea is that these buildings are stripped back to the essentials so the form comes through without any ridiculous (my word, not hers) fancy ephemera to distract you.

It fits the concept of “tabular rasa”: sweeping everything clean and starting over (I had to google that because I spelled it wrong). And it’s a very minimalist aesthetic: To achieve the most practically and aesthetically with the least possible means.

The other concept big in modernism was “form follows function” which in its simplest sense means the building should be designed so it can do what it’s meant to do. The Stack is an obvious example of this, I suppose, with its design that excludes the light so the archival artefacts aren’t damaged.

I tried to take notes but it’s impossible to do that and make photos at the same time AND listen to the person talking. (Can anyone tell me what “Groused Harvey” is supposed to mean? I wrote that in my notes and I have no idea!)

Bronwen spoke about glass curtain walls, of which this is Tasmania’s first example. She noted that this type of wall is non-structural; it is ‘pinned’ to the slabs, which themselves are built on columns which give the structural support. This is unlike older architecture, which is built brick-on-brick, put in a window and keep building. (Reminds me of my Lego days.)

A problem with these structures today is that this is very thin, light glass that was intended to deliver natural light and warmth into the building, accompanied by flexible “shape-shifting interiors” that could easily be altered to the required layouts.

But open plan offices suck (again, my words), and the glass isn’t exactly thermal glass, so it’s not super efficient.

The building, like many others of this era, is elevated, and with so much glass it appears light and weightless, almost like it’s floating, in direct contrast to its grounded heavy neighbour, the Stack. I can’t say I’d ever paid attention but Bronwen pointed out how the building is set back from the street front and it sits at a slightly different angle to the street.

With the building sitting above the ground there is potentially a great public space at street level. It’s a car park, which is not great use of the space, but, as Bronwen said, in this era everything was being designed around the “car is king” principle. (I don’t think much has progressed there . . . though there are shifts that are upsetting car drivers, so there is hope for us urban walkers.)

After stopping to admire the buildings from Murray Street, we headed down the road for the next stop on the tour.

To be continued . . .

In my other life, I’m preparing for the Point to Pinnacle walk to the summit of kunanyi/Mt wellington.

It’s a 21 km walk, which means I need to go out and walk a lot. Preferably up hills.

Last Saturday, I found myself in South Hobart so I took the opportunity to explore and climb hills. Well, one hill.

I only had my phone camera with me but I got some photo ideas as I made my way to Sandy Bay via Dynnyrne.

Macquarie Street

Macquarie Street

Macquarie Street

I didn’t realise until after I’d got back home from the Sydney trip that there was a companion to the Randwick Art Deco walk for the neighbouring suburb of Coogee.

That’s cool. I have somewhere new to explore next time I’m in the area.

I spent only a couple of hours in Coogee this time. It involved a walk down Coogee Bay Road, fish and chips on the beach, and the return walk up a back road that ended up in St Pauls Street in Randwick.

I was going to explore more the next day but the rain put an end to that idea.

After I’d spent more than an hour with Town Hall House, I wandered around briefly before deciding to call it a day.

First was the entrance to this building in Druitt Street, which was once, according to the real estate website, Australia Post’s central agency warehouse and also a gym operated by Madonna.

And I couldn’t help this photo of the Western Distributor coming off the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

I did come back into the city later in the week, to visit the Art Gallery of NSW.

I wrote about what I saw there on my travel blog.

While I was making my way back to the city, I saw this building from Hyde Park, which I later found out was 201 Elizabeth Street, a 38-storey building that is about to be redeveloped.

In the 1880s, this site was occupied by a five-story tobacco factory, which was demolished in the 1928 for a T&G Building designed by A&K Henderson. At 68 metres, it was the tallest building in Sydney at the time. That building was in turn demolished in 1975, with the current building completed in 1979. (Urbis, 2016)

Walking though the city I was surprised at how many of the older buildings were scaffolded and being redeveloped. I wondered how many of them were featured in the Sydney Modern and Sydney Inter-War walking tours and how many I wouldn’t have been able to see if I had gone looking for them.

One that wasn’t was the Commonwealth Bank building in Pitt Street and Martin Place. This is the building that the Commonwealth Bank used on its money boxes.

It was built in 1916 and was the first fully steel-framed structure in Sydney.

According to Sydney Inter-War, the building had a major addition from 1929-1933 along Pitt Street (not pictured) and again in 1965 along Martin Place, which can be seen at the back of the photo.

That was the end of my Sydney city adventures. I’m happy with what I saw on my two trips into the city, even if some of it was shrouded.

I’m never sure if Sydney actually is a more complicated city than Melbourne, but it seemed to be a lot harder to find buildings in the Sydney books than it had been in Melbourne. It might be that I’m geographically challenged. It’s been more than once I’ve headed off in the opposite direction to where I’m supposed to be going in Sydney, and I would have ended up on the tram back to Circular Quay if I hadn’t looked at the signs on the platform as the tram was arriving.

Sydney racetracks run backwards so maybe everything else there does too!

I suspect it’s more likely to be me though.

When I left off last time, I was walking off the Sydney Harbour Bridge, hoping the scaffolded building I could see (far left of the photo) wasn’t the AMP Building.

The little sandstone-looking building is the Fours Seasons Hotel, which I thought might have appeared in the Sydney Modern book. It doesn’t.

I couldn’t find out much about this building other than it was built in 1982.

Once you get off the bridge, there are a zillion lanes of traffic, and you can take the Cahill Walk back to Circular Quay through The Rocks.

Signs along the way tell about how the expressway was built and how much the area has changed.

Construction on the Cahill Expressway started in 1954, and it was built to divert through traffic away from the CBD. This road doesn’t sound like it has many fans. This article says it’s been described as “doggedly symmetrical, profoundly deadpan, severing the city from the water on a permanent basis, as well as “an eyesore, an unnecessary barrier between the city centre and the harbour foreshore and an inappropriate structure to have at the city’s point of entry”.

It says it is “extremely functional though rather ugly, and in a more environmentally and aesthetically conscious era would never have been allowed to be built”.

Ouch!

According to the signs, the construction took place across much of the “historic heart” of the city and resulted in many houses in The Rocks being demolished.

As you come off the walk, you can stand in the spot that was once Little Essex Street (and before that, Brown Bear Lane), which was demolished in 1954, and see what it would have looked like in 1902.

I made it back to Circular Quay and commenced my search for the AMP Building.

It was built in 1962, designed by Peddle Thorp and Walker. When it was completed, at 115 metres, it because Australia’s tallest building, breaking the height limit restrictions set in 1912. Sydney Modern says it used the precedent of Melbourne’s ICI House to do this. I’m not sure how that went down. Maybe it was “Melbourne broke their height limits so why can’t we, and we can make ours taller so we’ll win at tall buildings”.

I believe (at least in Melbourne’s case) it had something to do with the percentage of the area of the site the building was actually going to cover. So maybe that’s the precedent. For this building, a significant proportion of the site was to be public open space. It’s now a public transport space, which makes it congested and tricky to get around, but open space was the original intention.

I like my answer better.

According to the Cahill Expressway signs, the expressway “modernised the Circular Quay skyline, encouraging the construction of new skyscrapers”, and AMP house was obviously one of them.

As I had reluctantly suspected, it was indeed the scaffolded building.

This is what I saw when I got to 33 Alfred Street.

There’s boards underneath that provide some history of the building and explain what’s happening in the redevelopment (or, as they call it, re-sculpting).

Fortunately, the Tom Bass sculpture is still visible.

This sculpture depicts the goddess of Peace and Plenty, the male figure of Labour and a woman with a child. The AMP’s motto Amicus certus in re uncerta means “a certain friend in uncertain times”. This basic idea is a feature of other AMP buildings, including the one in Hobart.

According to Sydney Modern, the AMP Building is distinct because of its curved facade, “a feature which, along with its height, caused a surprising amount of controversy”.

It also had a roof-top observation deck that was closed when taller buildings came along.

Here’s what it used to look like, and what I’d been hoping to see.

Two out of two misses wasn’t a good start to the day!

I wandered around Circular Quay a bit longer and made the obligatory bridge photo.

I noticed markers on the ground denoting the line of the foreshore prior to settlement and development of the area, reminding me that in the context of this place and its original inhabitants, the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, what I was looking at was a minuscule faction of its history.

I could try and visualise what the AMP building might have looked like. It seems so small now. It’s hard to imagine it was once the tallest building here.

As I was deciding what to do next, I came across another Tom Bass sculpture on the side of a building, best seen from the adjacent set of steps.

Sydney Modern tells me this was originally on the side of the ICI building that was previously on the site.

Smaller than Melbourne’s ICI building, this was a glass curtain wall building designed by Bates Smart & McCutcheon (who also designed the one in Melbourne), constructed in 1957 and demolished in 1996.

Here’s a picture of the statue in situ. Information on Sydney’s ICI house seems to be a bit lacking because almost every search comes up with the Melbourne building. But here’s an archive photo of it being built.

By now I’d seen enough of Circular Quay and wondered if I wanted to find some more of the buildings in Sydney Modern and its partner, Sydney Inter-War 1915-1940. While I’d covered the Melbourne Mid-Century Modern tour in two days, these two tours were more logistically difficult.

For a start, I don’t know Sydney as well as I know Melbourne and have been known more than once to head off in the opposite direction to where I’m supposed to be. I’m not sure why, but Sydney has this disorienting affect on me. It’s probably something to do with how their horse races run the wrong way.

And there are two tours that overlap in a lot of places and Sydney’s big and I can never find anything . . . and I only went into the CBD for one thing, and I hadn’t seen it yet.

It was time to find what I’d come to see!

On my recent Sydney trip, along with the Randwick Art Deco Walk brochure and the Brutalist Sydney Map, I had with me the Footpath Guides Sydney Architectural Walking Guides. I have their Melbourne Mid Century 1950-1970 book and on one of my Melbourne trips I followed the route suggested in that book and photographed all 25 buildings. This had involved a couple of early morning starts staying in Melbourne CBD.

I decided I wasn’t going to do the full walks set out in either the Sydney Inter-war (1915-1940) or Sydney Modern (1950-1990) books but would pick out places that interested me. There was only one building that was on my “I must see this or the whole trip is ruined” list. I was going to find the others if I got the chance because I’d planned to spend most of the week in and around Randwick rather than in the CBD.

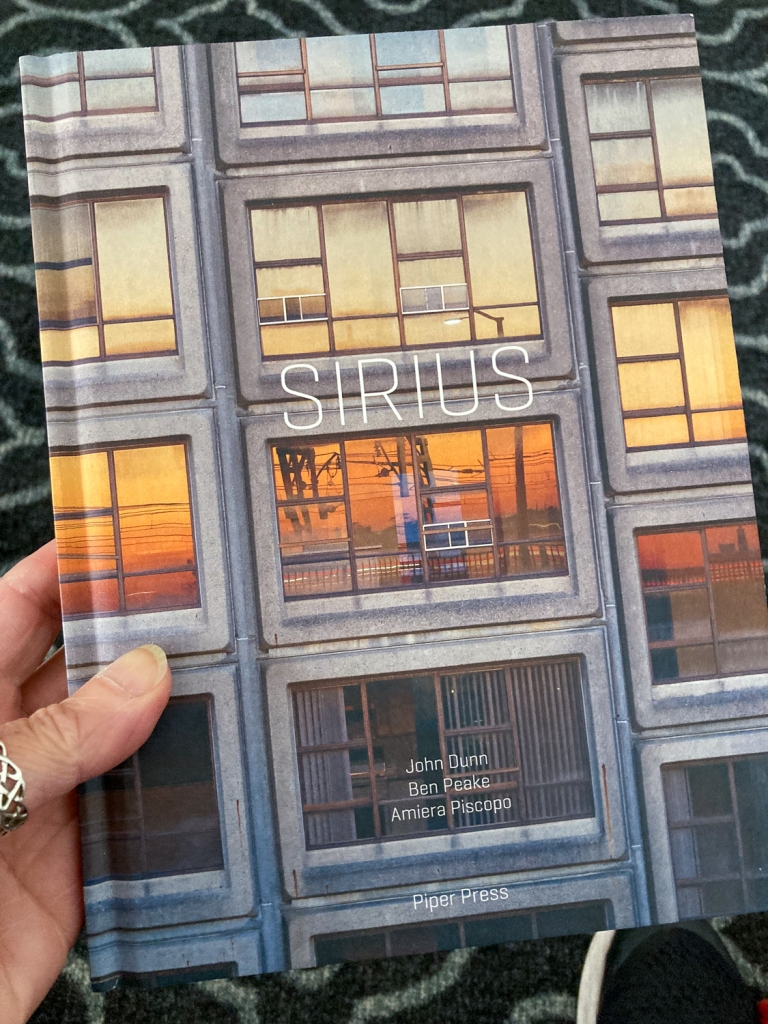

The Sydney Modern book mentioned the Sirius apartment building and the AMP building, both of which were around the Circular Quay area. I’d heard of both of them, so I made that my first stop on my CBD day. Circular Quay is a convenient light rail ride from either Randwick or Kensington so I had no trouble getting there.

The first structure that caught my eye (apart from the gargantuan cruise ship) was the Museum of Contemporary Art.

It was previously the Maritime Services Board building and replaced a much older building. It was planned in 1939 but was delayed because of shortages of labour and materials during the war. Work restarted in 1946 but further delays meant it wasn’t completed until 1952, by which time its design as considered somewhat dated.

The entrances are framed with pink Rob Roy granite, which came from quarries in Sodwalls, near Lithgow. The carved sandstone decorations under the clock tower (you can’t see them here) include a ship’s propeller, wheel and anchor signifying respectively the “driving force, guiding force and stability” of the Maritime Services Board.

Also, what visit to Circular Quay would be complete without a photo of the Sydney Opera House?

I wasn’t there to see either of those structures! Circular Quay was packed with unmasked people and I didn’t want to stay there, so my search for Sirius began. It’s on Cumberland Street, which would be easy for anyone who isn’t as geographically challenged as I am to get to from Circular Quay.

According to Sydney Modern, the NSW Housing Commission built the Sirius apartment complex over the period 1975-1980 to re-house public tenants who were displaced during redevelopment of The Rocks. It included a total of 79 apartments of various sizes, and catered for 250 aged and family residents.

Its architect was Tao Gofers, who was a Housing Commission architect at the time. He originally wanted to paint it white, but they ran out of money so (I think, thankfully) that never happened.

A “rare and fine example” of Brutalist architecture (according to the NSW Heritage Council), Sirius looked like this:

I knew it was in danger.

If I hadn’t already known, the bomb symbol next to the words “UNDER THREAT Demolition is imminent” in Sydney Modern (published in 2017) was difficult to miss.

The NSW government had announced in 2014 it would be selling the site to be redeveloped into luxury apartments. I hadn’t followed the story very closely but this was obviously very distressing for the residents of the complex, along with the broader community. They formed the Save Our Sirius Foundation to fight to save the complex.

In 2016 the NSW Heritage Minister refused to have Sirius listed as a heritage site, apparently because its heritage value was outweighed by its financial value to the government. The NSW Land & Environment Court didn’t agree.

By the end of 2017, however, Myra Demetriou was the only resident left at Sirius, and she moved out in February 2018 after the government finally put the complex up for sale. Myra passed away in 2021.

I’d heard there were plans to redevelop it into fancy boutique apartments rather than demolishing it but I hadn’t realised the work was actually underway until I (eventually) got there.

That was disappointing, and I’m sad I never got to see it as it was.

Because I’d taken the long way round, by the time I found Sirius, I’d walked under the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Continuing along Cumberland Street, past the bridge climb office, I found a random lift that went up to the bridge itself. I didn’t know you could walk on the bridge, so I went up to have a look.

The bridge construction started in 1924 and was completed in 1932. I found the bridge plaque, which mentions the firm Dorman Long and Company, who were the contractors for design and construction. My great grandfather worked for that company in the 1920s and my mother says he was involved in the bridge design. I have no reason to disbelieve this. He was a structural engineer who specialised in bridges. He moved to Tasmania in 1925, so his involvement must have been only at the very early stages. (Or he wasn’t involved at all and it’s just a family urban legend!)

I decided not to take the lift to the top of the pylon. The view was pretty good from where I was.

I didn’t want to go all the way across the bridge because I had other things to see. I’d been able to see a scaffold-clad building from the bridge and desperately hoped it wasn’t the AMP building which was also on my list to see . . .

I found this cool building on the way back. I have no idea what it is.

Coming off the bridge back down to The Rocks is the Cahill Walk, which accompanies the Cahill Expressway. I wondered if I was going to find myself in this Jeffrey Smart painting, but that’s further around the expressway.

I could see just one part of Siruis that hadn’t been covered over by the redevelopment work.

The lone block made me think of Myra’s story, and what it might have been like for her to be the last person living in the complex.

There was a cool view of the skyline.

Postscript for Sirius: I was at the Art Gallery of NSW later in the week and found a book about the struggle to save Sirius in the bookshop. It tells the history of the complex, from the Green Bans placed on The Rocks in the 1970s until the 2017 court ruling.

Continuing on the Randwick Art Deco Walk, today’s photos are from the last section of the walk including Alison Road, Bradley Street and Cook Street.

Continuing on the Randwick Art Deco Walk, today’s photos are from around Belmore Road, which is the main business area of Randwick.